In this guide, I’ll cover the basics of deploying a Rails application to Ubuntu 14.04 on a Digital Ocean box. This guide will work on non-Digital-Ocean boxes too, and it might work on different Ubuntu versions. Try it out and find out :)

If you find any mistakes in this guide, please let me know in the comments below.

In the guide, we’ll be using:

- ruby-install: To install a Ruby version system-wide.

- nginx: A webserver to serve our Rails application with.

- Passenger: The proxy between nginx and Rails which automatically starts + stops Rails application “worker processes”.

- Capistrano: A very helpful tool that automates your deployment workflow.

While you could serve traffic from your production site using rails s, there are many issues with that:

- It runs on port 3000, whereas most websites run on port 80.

- If it dies, you will need to restart it manually.

- It will crash under heavy load because the web server it uses (WEBrick) has not been designed for production use.

So instead, we’ll be using nginx and Passenger.

Before we can run our Ruby on Rails application on the server, we’ll need to install Ruby.

Installing a Ruby version

In order to install Ruby, we’ll need to install the build-essential package. This package gives us the build tools that we’ll need to compile Ruby.

We first need to make sure that our apt sources are up-to-date. If they’re not, installing the build-essential pcakage might fail. We will do this by logging into the machine as root, and then running this command:

apt-get update

Next, we’ll need to install the build-essential package itself:

apt-get install build-essential

With those tools installed, we will now install a Ruby version with the ruby-install tool. Follow the install steps for ruby-install (reproduced here for your convienience):

wget -O ruby-install-0.5.0.tar.gz https://github.com/postmodern/ruby-install/archive/v0.5.0.tar.gz

tar -xzvf ruby-install-0.5.0.tar.gz

cd ruby-install-0.5.0/

make install

We will now install Ruby 2.2.2 system-wide by running this command:

ruby-install --system ruby 2.2.2 -- --disable-install-rdoc

We’re installing it system-wide so that it’s available for all users on this machine. The --disable-install-rdoc tells Ruby to skip the part about installing RDoc documentation for Ruby on this machine. This is a production machine and we don’t need RDoc.

Eventually, we’ll be having each application have its own user on this machine. While we could use

ruby-installon a per-user basis, it makes much more sense (and is easier!) to have it on a system-wide level.

Once that command finishes running, let’s remove the ruby-install package + directory:

rm -r ~/ruby-install-*

It might make sense at this point to install Rails, but we should definitely let Bundler take care of that during the application deployment process. Let’s just install Bundler for now:

gem install bundler

Deploying the application

To deploy the application, we’re going to use a gem called Capistrano. Capistrano has been a mainstay of the Ruby community for some time now due to its flexibility and reliability.

With Capistrano, we’ll be able to (git) clone the Rails application to the server and run any necessary configuration steps that are required to get our application running, such as bundle install, rake assets:precompile, and configuring a database.

Creating a new user

The first thing to do is to create a new user on the machine where we’re deploying to for the application. This user will be sandboxed into its own directory, which means the application will only have access to that user’s home directory.

If we installed the application as root and Rails had a Remote Code Execution vulnerability, the box could get taken over by some malicious hackers.

Let’s create this new application user now:

useradd -d /home/rails_app -m -s /bin/bash rails_app

I’ve used rails_app here just as an example. You should use your application’s name.

The -d option specifies the home directory of the user and the -m option tells useradd to create that directory if it doesn’t already exist. The -s option tells it that we want to use the /bin/bash shell.

Next, we’ll want to make it so that we can connect to the server as this user. This is so that when we deploy the application, we do so as the user that we just created. If you’ve setup GitHub already, you probably already have setup an SSH key. If not, follow this excellent guide from GitHub.

To allow you to connect to the application server as the new user, we’ll need to copy over the public key (~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub) to the server. The easiest way to do this is to copy it over to root first. On your own personal computer, run this command:

scp ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub root@yourmachine.example.com:~/key

Then on the server, move the key over to the new user’s home directory:

mkdir -p /home/rails_app/.ssh

mv key /home/rails_app/.ssh/authorized_keys

chown -R rails_app /home/rails_app/.ssh

chmod 600 /home/rails_app/.ssh/authorized_keys

Once you’ve run those commands, you should be able to SSH into the machine as that user without requiring a password.

ssh rails_app@yourmachine.example.com

If you run ruby -v after connecting, you should see this:

ruby 2.2.2p95 (2015-04-13 revision 50295) [x86_64-linux]

This indicates that Ruby can be found for your user, and that we can proceed to deploying the application.

Before we move onto the next section, we’ll need to generate a “deploy key” for this user. This will be used by GitHub to grant this user access to the repository on GitHub.

We will generate that key by running this command on the server as our application’s user:

ssh-keygen -t rsa

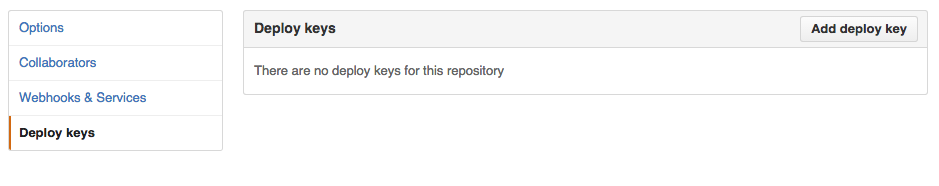

On our repository on GitHub, we can go to “Settings”, then “Deploy Keys” and add a new deploy key:

In the “Title” we can put whatever we feel like, but in the “Key” field we’ll need to put the contents of the ~/.ssh/id_rsa.pub file that the ssh-keygen command generated. Create the new deploy key now.

We’ll need to set Git up on this machine so that we can clone the repo to test it out, and later to actually deploy the application. Let’s install it now with this command ran as root:

apt-get install git-core

Switch back to the rails_app user. We can test if this key is working by running git clone git@github.com:you/example_app.git (or whatever your repo is). If the key is setup correctly, then the clone will work.

Deploying with Capistrano

Next, we’ll automate the deployment of our code to the server with Capistrano. We can install Capistrano as a gem dependency of the application by adding these two lines to the Gemfile:

gem 'capistrano-rails'

gem 'capistrano-passenger'

We can then run bundle install to install capistrano-rails and capistrano-passenger and their dependencies. To install Capistrano into our application, we’ll need to run bundle exec cap install. This will install a couple of files in our application that will be used to configure how Capistrano deploys the application to our servers.

The first of these files is config/deploy.rb. Near the top of this file are these two lines:

set :application, 'my_app_name'

set :repo_url, 'git@example.com:me/my_repo.git'

We will need to change the application to match the name of our application (rails_app is mine, but your application name is different!), and change the repo_url to be the git@github.com URL for our application. We should also change the path of the application so that it deploys to the home directory of the user:

set :deploy_to, '/home/rails_app/app'

Next, we’ll need to tell Capistrano where to deploy the application to. We can do this by adding this as the first line in config/deploy/production.rb:

server 'app.example.com', user: 'rails_app', roles: %w{app db web}

Finally, we’ll need to tell Capistrano to run bundle install when the application is deployed, as well as to run the migrations and compile the assets. We can do this by uncommenting these lines in Capfile:

require 'capistrano/bundler'

require 'capistrano/rails/assets'

require 'capistrano/rails/migrations'

require 'capistrano/passenger'

Here’s what each of those do:

capistrano/bundleris responsible for runningbundle install(with some fancy deployment options as you’ll see later) during an application deployment. This ensures that the gems on the server are up to date with whatever’s specified in theGemfile.lock.capistrano/rails/assetsis responsible for precompiling the assets upon deploy.capistrano/rails/migrationsis responsible for running the migrations for a new release (if any) during a new deploy.capistrano/passengerwill restart the application on every single deploy, ensuring that only the latest code is running.

This sets up most of the Capistrano configuration. There’s a couple more pieces that we will address as they come up.

There’s two more thing to do before we can deploy the application to the server: we’ll need to install the development headers for whatever database system we’re using and we’ll need to install a JavaScript runtime.

Database setup

Install one of the following packages as the root user on that machine:

- By default, a Rails application uses SQLite3. To install SQLite3’s development headers, run this command:

apt-get install libsqlite3-dev

- If you’re using MySQL, run:

apt-get install libmysqlclient-dev

- If you’re using PostgreSQL, run:

apt-get install libpq-dev

If you’re using MySQL or PostgreSQL, you’ll need to install their servers.

- For MySQL, the package to install is

mysql-server. - For PostgreSQL, the package to install is

postgresql-9.3

JavaScript runtime

My preferred JavaScript runtime is the nodejs package. You can install it with apt-get install nodejs. This package will be used by the server to during rake assets:precompile to precompile the JavaScript assets.

Deploying the first version

We can now run bundle exec cap production deploy to deploy our application to our server. The first deploy might be a bit slow while all the gem dependencies are installed on the server. Patience is required for this step.

When it’s complete, the final line should look like this:

INFO [9fa64154] Finished in 0.194 seconds with exit status 0 (successful).

Capistrano has set up your application directory and it has deployed it to a directory at /home/rails_app/app/releases/<timestamp>. This directory is unique to this release so that you may choose to rollback (with bundle exec cap production rollback) if something goes wrong.

Capistrano started out by cloning your application into the directory it created. It then:

- Ran

bundle installto install your application’s gem dependencies. - Ran

rake assets:precompileto precompile your application’s assets. - Ran

rake db:migrateto migrate the production database for the application up to the latest version.

The next step Capistrano will do is symlink the release directory to /home/rails_app/app/current. This is so that we have a sensible name with which to access the current release of our application.

At the end of all of that, it will also check the number of releases in the application directory. If there are more than 5, it will delete the oldest ones and keep only the 5 most recent. Again: these are kept around so that you may choose to rollback if something goes wrong.

With the application deployed, let’s get it to serve our first production request by installing nginx + Passenger and then configuring them.

Installing nginx + Passenger

We can install a standalone edition of nginx using the Passenger installer, which massively simplifies what we’re about to do. Without it, we would need to install nginx and Passenger, then we would need to configure these to work with each other.

Before we can install that, we’ll need to install one more package:

apt-get install libcurl4-openssl-dev

This installs Curl development headers with SSL support, which Passenger uses during the installation process.

To install Passenger, we will run gem install passenger, as root.

Next, we’ll need to install Passenger and nginx, which we will do by running passenger-install-nginx-module and following the steps. We want to select Ruby when it prompts us for which languages we’re interested in, of course. When it asks if we want Passenger to download + install nginx for us, we’ll select the first option; “Yes: download, compile and install Nginx for me.”

This is another part where we’ll need to wait a bit while Passenger compiles all the things it needs. Once it’s done, it will tell us to put this configuration in our nginx config:

server {

listen 80;

server_name www.yourhost.com;

root /somewhere/public; # <--- be sure to point to 'public'!

passenger_enabled on;

}

The listen directive tells nginx to listen for connections on port 80. The server_name directive is the address of your server, and you should change this from www.yourhost.com to whatever your server is. The root directive tells nginx where to find the application. The passenger_enabled directive should be very obvious.

Open /opt/nginx/conf/nginx.conf and delete the server block inside the http block, and replace it with the above example. Update the values in the example to be specific to your application.

You can start nginx by running:

/opt/nginx/sbin/nginx

If we try to access our application now, we’ll see a “Incomplete response received from application” error. In order to diagnose one of these, we can look in /opt/nginx/logs/error.log, which will tell us what caused that:

*** Exception RuntimeError in Rack application object (Missing `secret_token` and `secret_key_base` for 'production' environment, set these values in `config/secrets.yml`) (process 5076, thread 0x007fd841f79d58(Worker 1)):

It’s telling us that we’re missing the secret_token and secret_key_base for the production environment in config/secrets.yml. If we look at our application’s config/secrets.yml, we’ll see indeed that this is missing:

development:

secret_key_base: [redacted]

test:

secret_key_base: [redacted]

# Do not keep production secrets in the repository,

# instead read values from the environment.

production:

secret_key_base: <%= ENV["SECRET_KEY_BASE"] %>

While the comment above the production key (and the code itself!) says to read it from the environment, I personally think it’s easier to have a config/secrets.yml with the secret key kept on the server itself, and then have that copied over on each deploy.

Generating a secret key

To that end, we will put a config/secrets.yml in the /home/rails_app/app/shared directory and tell Capistrano to copy that file over during deployment. We’re creating the file in the shared directory because it’s going to be a file that is shared across all releases of our application.

To generate the secret_key_base value for the production key inside the new config/secrets.yml file, we will run rake secret inside our application. This will give you a very long key, such as:

eaccffd1c5d594d4bf8307cac62cddb0870cdfa795bf2257ca173bedabc389a399b066e3b48cc0544604a4a77da38b9af4b46448fdad2efac9b668a18ad47ddf

Don’t use this one, because it is not secret! Generate one yourself.

When you’ve generated it, log into the server as rails_app and create a new file at /home/rails_app/app/shared/config/secrets.yml with this content:

production:

secret_key_base: "<key generated by rake secret>"

Next, we’ll need to uncomment the line in config/deploy.rb for the linked_files option.

set :linked_files, fetch(:linked_files, []).push('config/secrets.yml')

We’ve taken out config/database.yml for the time being just so we can confirm that we’re passed this secrets.yml issue. After we’ve dealt with that, we’ll come back and look at creating a shared database.yml.

Let’s run another deploy now with bundle exec cap production deploy. This deploy should fix our secrets.yml problem. Making a request to the application might work now if you’re using SQLite3. If not, then you’ll need to wait until the next section is over before that will all work.

Database configuration

If you’re not using SQLite3 in production, then you’ll need to setup a database for your application. This guide will only configure PostgreSQL, since that is what I personally am most familiar with.

The first thing that you will need to do is to create a database + user in PostgreSQL for this user. To do that, run these commands:

sudo su postgres

createdb rails_app

createuser rails_app

While the database name can be different to the username, the username that we use for PostgreSQL must be the same as the user that you use to SSH onto the server to deploy the application. When the application tries connecting to the database, it will do it using the same name as the user that the application runs under; which has been

rails_appin this guide.

We switch to the postgres user as it has superuser rights on our database which means it can execute the createdb and createuser commands. The root user of the machine cannot run these commands itself. You’ll need to switch back from the postgres user back to root, which you can do by running exit.

Once we’ve run those commands, we can test to see if it’s working by running psql as the rails_app user. If it is working, then we will see a psql console like this:

psql (9.3.9)

Type "help" for help.

rails_app=>

Great! Now we can setup the database configuration for the application. The first step is to change the database engine that the application uses in its Gemfile from sqlite3 to the PostgreSQL gem, pg:

gem 'pg'

Next, we will need to run bundle install to update our application’s dependencies. We will need to ensure that we change our local config/database.yml to use PostgreSQL as well. You’ll want to be using the same database software locally and on the server, as that means that you have identical environments across the different machines.

The next step is to put a config/database.yml in the /home/rails_app/app/shared directory which only contains a production key:

production:

adapter: postgresql

database: rails_app

We can copy this file over on deploy by updating config/deploy.rb and changing the linked_files line to this:

set :linked_files, fetch(:linked_files, []).push('config/database.yml', 'config/secrets.yml')

We’ll need to commit the changes to the Gemfile + Gemfile.lock before continuing here.

The application will now work after one more run of bundle exec cap production deploy. Try it out yourself by visiting your app.

Your app should now be deployed to your server. Go ahead and try it out.

Conclusion

Your application is now deployed, but the fun doesn’t stop here. You may need to tweak the PassengerMaxInstances configuration setting inside the VirtualHost block for your application to increase or decrease the amount of instances running on the machine, depending on how much free RAM you have. If you’re running out of RAM, decrease this number. It entirely depends on the application, so just experiment to find out what value suits you.

The entire Passenger Users Guide is a good read for other bits of tweaking too.

You may wish to setup exception tracking for your application now that it has been deployed to production, and for that I recommend Rollbar. It’s very easy to setup for any Rails application and they have instructions on how to do that on their site.